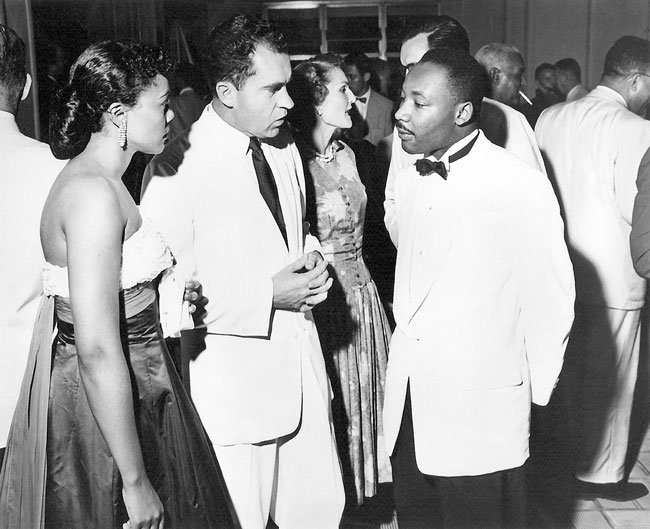

Griffith J. Davis. First Meeting of U.S. Vice President Richard Nixon and Martin Luther King, Jr. March 6, 1957. Black and white inkjet print. 12 1/8 x 11 in. Griffith J. Davis Photographs and Archives.

STILL HERE: The Griffith J. Davis Photographs and Archives in Context

January 22 – March 06, 2021

USF Contemporary Art Museum West Gallery

Still Here is curated by Dorothy M. Davis, President of Griffith J. Davis Photographs and Archives; Christian Viveros-Fauné, CAM Curator at Large; and Noel Smith, CAM Deputy Director and Curator of Latin American and Caribbean Art; and organized by USFCAM.

ONLINE EXHIBITION

Exhibition Home // Foreword + Acknowledgements // Introduction by Dorothy M. Davis // Essay by Christian Viveros-Fauné

STILL HERE: The Griffith J. Davis Photographs and Archives in Context

I been scarred and battered.

My hopes the wind done scattered.

Snow has friz me,

Sun has baked me,Looks like between 'em they done

Tried to make meStop laughin', stop lovin', stop livin'--

But I don't care!

I'm still here!—Langston Hughes, “Still Here”

The image of a smiling Nat King and Marie Cole awaiting a flight to Acapulco for a Mexican honeymoon; a portrait of artist Hale Aspacio Woodruff in Los Angeles hard at work on a mural titled The Negro in California History—Settlement and Development; a forlorn picture of Emperor Haile Selassie feeding the ducks outside his Imperial Palace in Addis Ababa; a groundbreaking photo of the first meeting between Vice President Richard Nixon and Martin Luther King, Jr. in Accra, Ghana. These are just some of the images that make up an archive of 55,000 photographs and countless documents and memorabilia Griffith J. Davis (1923-1993) bequeathed to his family and the world. Together they chart a parallel cultural and political history of two continents in black and white, and sometimes in color.

Photojournalist, diplomat, and filmmaker, Davis spent a lifetime keeping company with prominent “legislators” of two distinct types. The first were presidents, political leaders, and diplomats from Africa and the U.S. who launched decisive independence and civil rights struggles beginning in the 1950s—among them MLK, Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, NAACP Chairman Julian Bond, Ghanian Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah and Presidents William Tubman of Liberia and Habib ibn Ali Bourguiba of Tunisia. The second were figures the English Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley would have dubbed “the unacknowledged legislators of the world”—artists, poets, philosophers, writers and musicians—with whom Davis regularly rubbed elbows after befriending poet Langston Hughes in 1947.

The exhibition Still Here: The Griffith J. Davis Photographs and Archive in Context brings together Davis’ images of these celebrated personages from the intertwined worlds of politics and culture, while also addressing the life and work of this pioneering Black figure. In addition, the exhibition places Davis’ images and diplomatic work in context with current and historical artworks made by modern and contemporary Black artists from the United States and Africa—the better to understand the connections between them and the profound cultural and political moment Davis fixed in the amber of analog photography.

In some cases, the inclusion of contemporary artworks serves to chronicle the ongoing social and cultural impact of liberation struggles on both continents. Included in the exhibition are photographs, collages, lithographs and digital prints from artists Romare Bearden, Emory Douglas, Jacob Lawrence, Deana Lawson, Zanele Muholi, and Hank Willis Thomas. Douglas’ 1970s-era graphic depictions of urban guerrillas extend the nominal discourses of Africa’s anti-colonial struggle and Civil Rights in the U.S. by popularizing the militancy of the Black Panther Party, itself inspired by intellectuals like Nkrumah (his book I Speak of Freedom was listed third on the Panther’s official 1968 reading list for prospective members). The inclusion of Thomas’ more recent prints proves another sharp counterpoint. Besides providing examples of rejiggered corporate advertising—not unlike that carried in the issues of Time and Life in which Davis published—the celebrated American artist is the son of renowned curator and scholar Deborah Willis. A leading authority on Black American photography, Willis has long considered Griff Davis to be one of her mentors.

Clear-eyed in their candor and composition, Griff Davis’ photographs speak directly to our time with the immediacy of origin stories. Take his 1948 picture of Thurgood Marshall. A photo of the Chief Counsel for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, it features a confident Marshall poised to defend Ada Lois Sipuel in her landmark case against the University of Oklahoma Law School—an important precursor to Brown vs. Board of Education (the photograph is currently in the archives of the U.S. Supreme Court). Davis’ posed photograph of painter Hale Woodruff in shirtsleeves also contains historical multitudes: a panoramic depiction of the history of Black life and achievement in California from the years 1527 to 1949, Woodruff’s mural was commissioned by Golden State Mutual Life Insurance—the first Black owned insurance company established west of the Mississippi.

But no photograph conveys Davis’ ability to picture a parallel Black global history as much as his rare image of Nixon and MLK, Davis’ childhood friend and Morehouse College classmate. Taken in 1957 during the independence celebrations in a newly sovereign Ghana—Davis attended as both a friend of Nkrumah’s and as a representative of the United States Information Service (USIS)—the photo is important precisely because it could not be reproduced in “separate but equal” America. Not published until January 19, 2020, by The Tampa Bay Times, the photo captures two of the 20th century's major protagonists, America’s better and worse angels, in a single frame—while perfectly encapsulating the hidden history of Black self-representation in America. Again and again, Griff Davis’ photographs perform feats of revelatory photojournalism: they pull back the curtain on history and let the light stream in.

Christian Viveros-Fauné

Curator-at-Large

USF Contemporary Art Museum

Still Here is supported by a USF Understanding and Addressing Blackness and Anti-Black Racism in Our Local, National, and International Communities Research Grant; Susana and Yann Weymouth; Mort and Sara Richter; Major Sponsor The Stanton Storer Embrace the Arts Foundation; and the Florida Department of State.